Body People Yeah, Body People Let Die to See You Baby Baby...

The tragic tale of Mt Everest's most famous dead body

Mount Everest is home to more than 200 bodies. Rachel Nuwer investigates the sad and little-known story behind its most prominent resident, 'Green Boots' – and discovers the disturbing effects this deadly mountain can wreak on the mind and body.

T

This is part of BBC Future's "Best of 2015" list, our greatest hits of the year.

-

"It is clear that the stake [the mountaineer] risks to lose is a great one with him: it is a matter of life and death…. To win the game he has first to reach the mountain's summit – but, further, he has to descend in safety. The more difficult the way and the more numerous the dangers, the greater is his victory."

- George Mallory, 1924

As though napping, the climber lies on his side under the protective shadow of an overhanging rock. He has pulled his red fleece up around his face, hiding it from view, and wrapped his arms firmly around his torso to ward off the biting wind and cold. His legs stretch into the path, forcing passers-by to gingerly step over his neon green climbing boots.

His name is Tsewang Paljor, but most who encounter him know him only as Green Boots. For nearly 20 years, his body, located not far from Mount Everest's summit, has served as a grim trail marker for those seeking to conquer the world's highest mountain from its north face. Many have lost their lives on Everest, and like Paljor, the vast majority of them remain on the mountain. But Paljor's body, thanks to its prominence, came to be one of the most well-known.

"I would say that really everybody, especially those climbing on the north side, knows about Green Boots or has read about Green Boots or has heard somebody else talking about Green Boots," says Noel Hanna, an adventurer who has summited Everest seven times. "About 80% of people also take a rest at the shelter where Green Boots is, and it's hard to miss the person lying there."

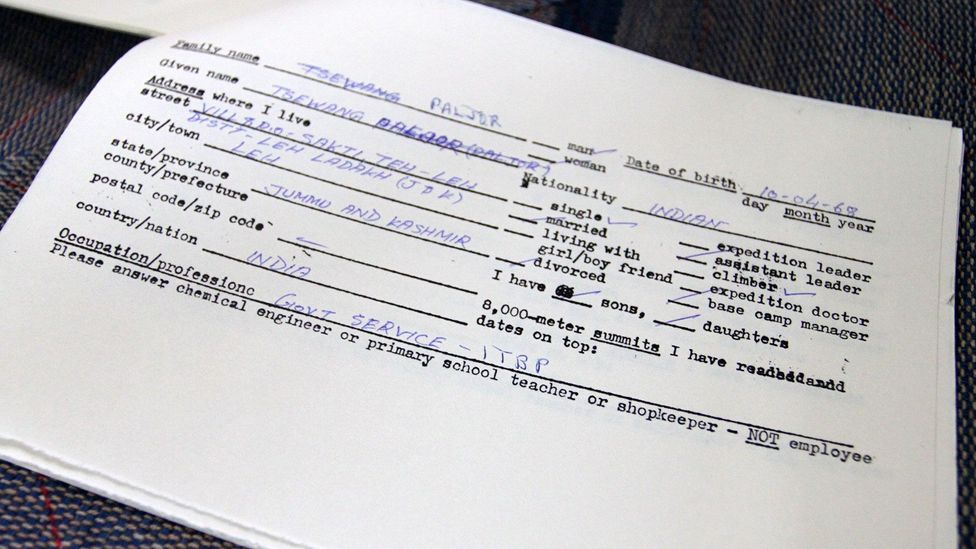

With Paljor's death came a wave of controversy, including whether he and his two teammates died because other climbers, in their own lust to reach the peak, callously ignored their signs of distress. Scant information is available about the man behind the nickname, however. Type "Green Boots" into a Google search and you will learn that Paljor, along with climbing partners Tsewang Smanla and Dorje Morup, perished in the 1996 storm immortalised in Jon Krakauer's best-selling book Into Thin Air and, more recently, the big-budget thriller Everest. Paljor, Wikipedia tells you, was a member of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police, and was just 28 years old when he lost his life.

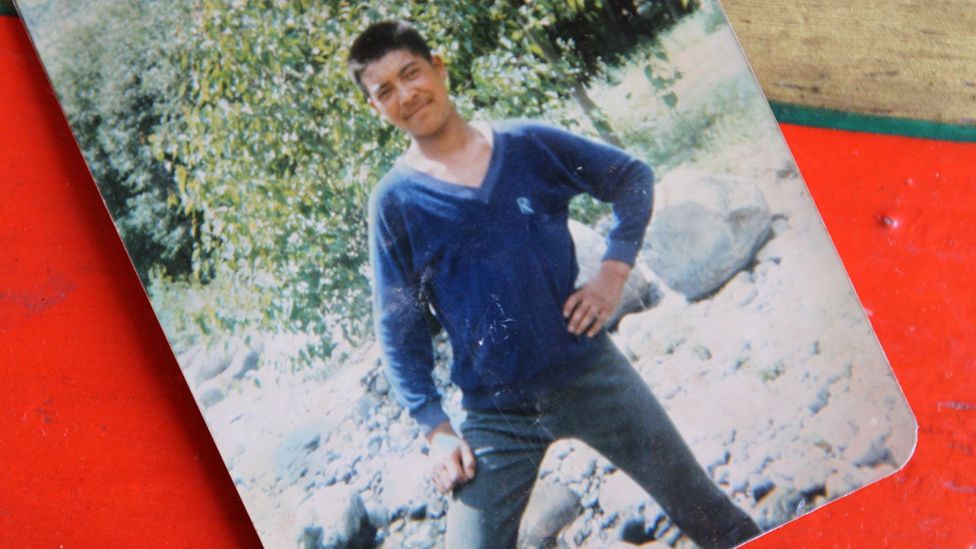

Tsewang Paljor, in younger days. Photographs by Rachel Nuwer.

I admit to feeling a certain morbid curiosity at the thought of Paljor and all the other fallen climbers on the mountain, stranded far from loved ones and frozen in time, forever displaying the moment of their death. But more than a fixation on the macabre, I wished to know the story of the handsome young man in the green boots – especially the circumstances that could allow him to remain on the mountain for so many years.

I was also intrigued by what extreme altitude can do to the human body and mind, and the unexpected impact it can have on the decisions – and even ethics – of a person. But ultimately, I wanted answers to another, more pressing query; one that has been raised countless times but seems to evade explanation: why climb this mountain at all? Why gamble your life on its unforgiving slopes? According to the records of Alan Arnette, a mountaineer based in Colorado whose blog is a trusted source of Everest information, from 1924 to August 2015, 283 people have died on the mountain – 170 foreigners and 113 Nepalis – leading to an overall deaths-to-summit ratio of about 4%. How is it that so many people still see this endeavour as worthwhile?

My desire to answer these questions – in a two-part in-depth series for BBC Future – led me down a rabbit hole of psychology, ethics and climbing culture; to the doorsteps of mountaineering legends and broken-hearted parents alike; to sources spanning Fukuoka, California and Kathmandu. This is my attempt to make sense of what I found.

A cheerful place

As the plane lifts off and heads north from New Delhi, the city's smog, congestion and sprawl quickly fade from view, replaced by brown, rural flatness that in turn morphs into green hills and terraced fields.

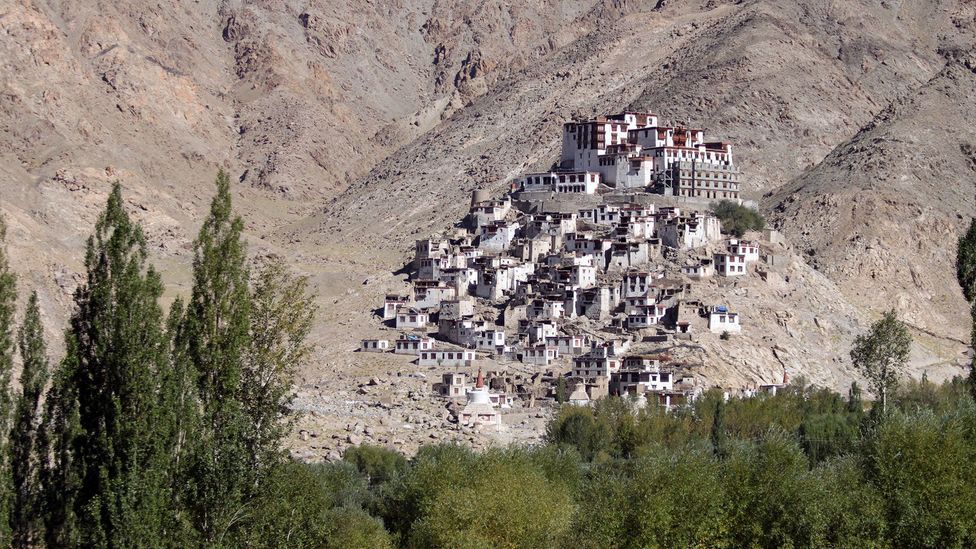

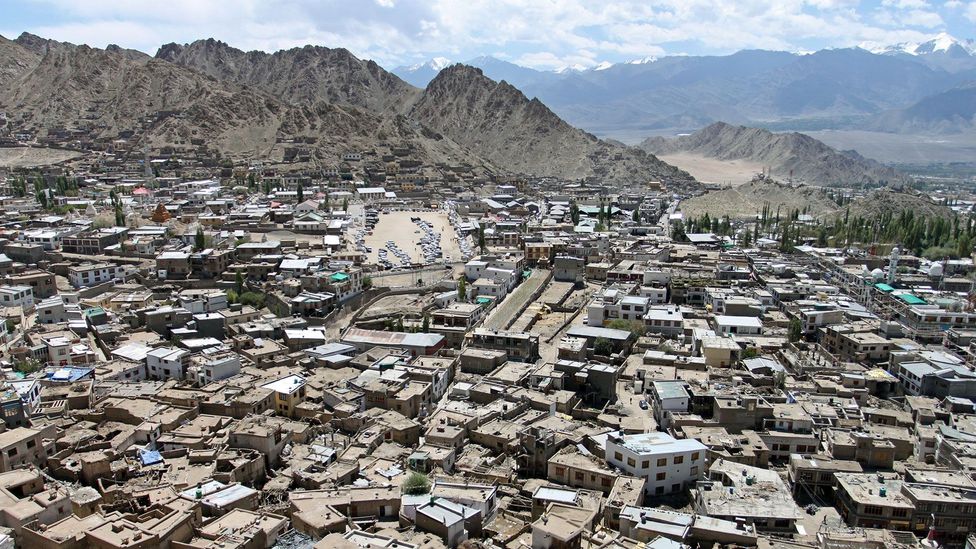

Ladakh, "owner of passes," which lies in the shadow of the Great Himalayas

The landscape, however, has only begun to grow in scale and splendour. Hills climb to ever-greater heights, shaking themselves free of villages, fields and vegetation – and then, any remnants of life. Jagged, snow-kissed mountain peaks stretch ever higher, as though trying to pluck our tiny vessel from the sky. Here and there, a valley river punctuates the monochrome landscape with a ribbon of green, a lifeline in an otherwise impossibly inhospitable environment.

We've almost reached our destination. The plane begins its descent, and the captain's voice crackles over the intercom: "I hope all of you have left all of your worries behind in Delhi, so you can have a great time in this cheerful place."

We're in the region of Ladakh, "owner of passes," which lies in India's far north, in the shadow of the Great Himalayas. It's early September, when the days are bright and warm but nights are already creeping below 0C.

It was here, in this high altitude desert at 3,800m (12,500ft), that Tsewang Paljor was born on April 10, 1968. He grew up in Sakti – "the golden throne" – an idyllic valley village of whitewashed houses, barley fields and poplar trees.

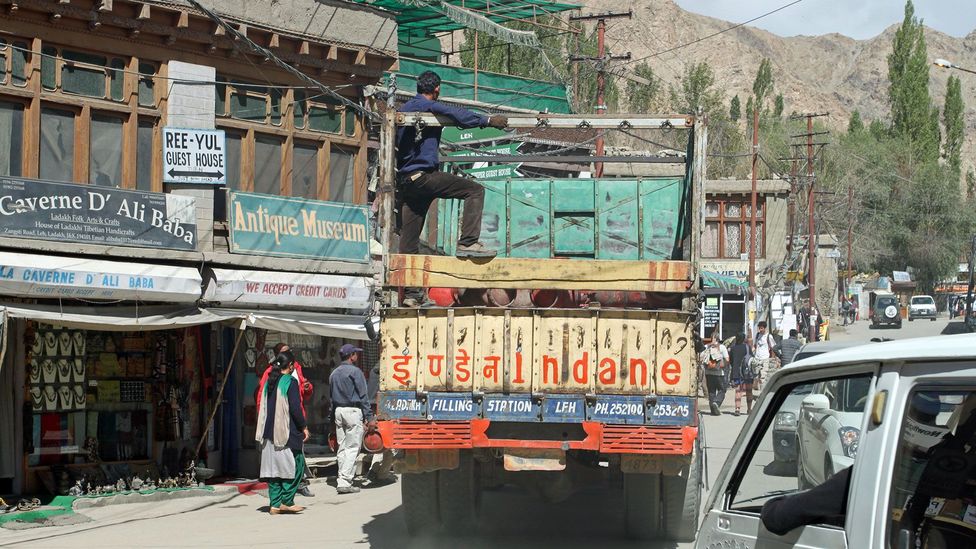

Leh, Ladakh's dusty capital

We set out for Sakti early on a Wednesday, following the course of the brilliant blue Indus River, passing breathtaking mountainside monasteries, dusty roadside diners and otherworldly plains of rock and barren earth. I travelled with Tsultim Dorjey, a sociologist and guide, who is serving as my local lifeline.

We had not contacted Paljor's family ahead of time, believing our odds of convincing them to speak with us about such a sensitive subject would be greater if we described our mission in person. Now, I was plagued by doubt. Would they refuse to speak with us? Would they be offended? Would anyone even be home?

We passed dusty, otherworldly plains on our journey

Passing remote villages on the way to Paljor's home

About an hour after leaving Leh, we were getting close. Tsultim jumped out of the car, approaching an old man fingering some Buddhist prayer beads on the side of the road. Asking the man where we could find the Fana farm – Paljor's family surname – the man began gesturing emphatically down the road. In a place like Sakti, populated by just 300 or so households, everyone knows everyone else. "It's not far now," Tsultim reported, climbing back into the car.

Getting directions in Ladakh

Minutes later, we arrived at a brown gate, in front of an attractive two-storey home with large windows and fluttering Tibetan prayer flags adorning the roof. "This is it," Tsultim said. "Fingers crossed."

My stomach churned as we approached the front door, past a garden brimming with petunias, marigolds and daisies and a yellow dog, who gazed lazily at us from a sunny spot.

Arriving at the home of Paljor's mother, unsure what to expect

My fears were alleviated, however, the moment Tashi Angmo, Paljor's mother, opened the door. At 73, her twinkling eyes and smiling face appeared a decade younger. Radiating grandmotherly warmth, she greeted us energetically – "Julay!" – and beckoned for us to come inside, not even asking who we were or why we were here.

We made our way into the sitting room, lined with couches, ornately carved tables and poster-size photos of her grandchildren. After fetching a pot of steaming tea and a plate of biscuits, she and Tsultim exchanged niceties for several minutes. I didn't have to understand Ladakhi, however, to recognise the moment when Tsultim revealed the true purpose of our visit. Tashi Angmo's face, until now all smiles, abruptly went slack, her numbed expression speaking of years of accumulated grief and loss. Yet when Tsultim asked if we could proceed with the interview, she said yes.

The house of Tsewang Paljor's family

A quiet middle child with five siblings, Paljor was known in the village for his polite, compassionate manner. He had a big heart and natural kindness. Though good-looking, even as a teen Paljor never had a girlfriend – he was simply too shy. He once told his brother that he was more interested in dedicating his life to something bigger than himself than in getting married.

As the eldest son, Paljor no doubt felt pressured to provide for his family, which was struggling to make ends meet at their modest farm. So after completing 10th grade, he quit school and tried out for the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), whose sprawling campus was located in nearby Leh, Ladakh's dusty capital. Formed in 1962 in response to increasing hostilities from China, the men who serve in that armed force specialise in high altitude landscapes – a necessity given that India's border with its domineering neighbour stretches across the Himalayas. To Paljor and his family's delight, he made the cut.

Tashi Angmo, with her son's possessions

Tashi Angmo was very supportive of his position at the ITBP, but he sensed that her support would only extend so far – certainly not to the top of the world's highest mountain. So when he was selected to join an elite group of climbers who would undertake a risky but grandiose mission – to become the first Indians ever to summit Everest from its north side – he chose not to reveal his true destination to her. "He told a small lie, that he was going to climb a different mountain," his mother says. "But he also told some friends what he was actually doing, and word got back to us."

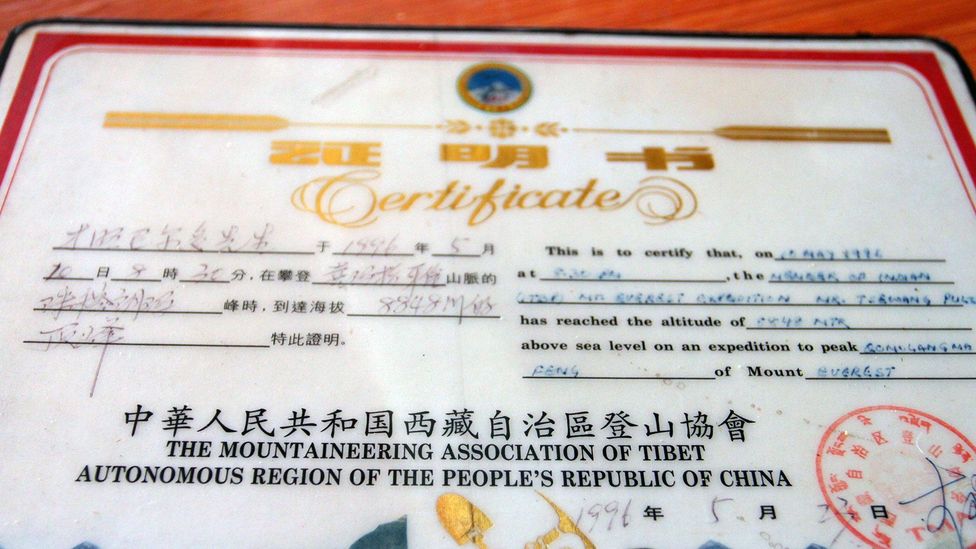

Although Paljor's career already included many successful summits of other peaks, and Tashi Angmo's shelves brimmed with his certificates and awards, Everest struck her as being an exceedingly dangerous place. She implored her son not to go, but he told her he had to. "He must have thought, if he climbs Everest, it will bring benefits for his family," she says.

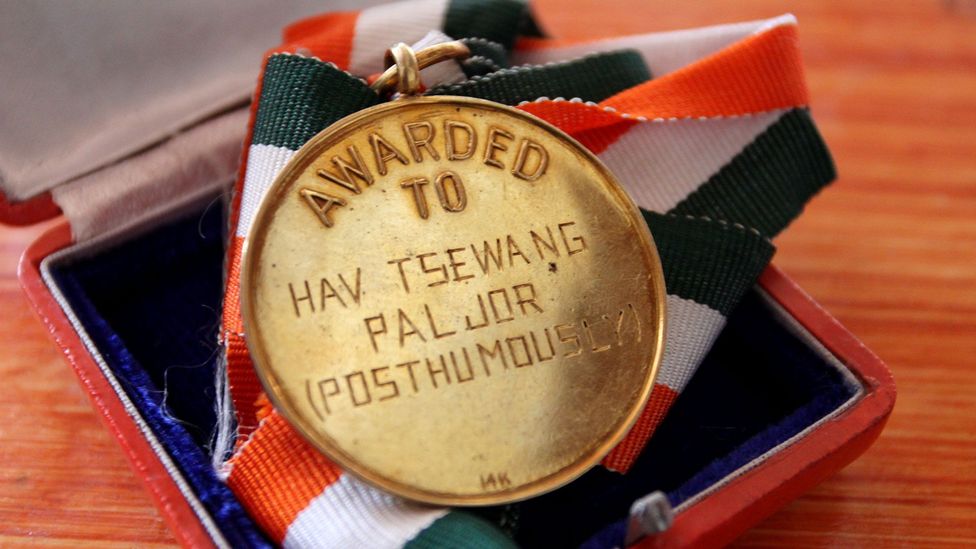

A certificate marking Paljor's ascent

But younger brother Thinley Namgyal was not worried. His brother was the strongest person he knew. "When he came home for holidays, we used to play around and kick his tummy, because it was like a rock," he says. "I always thought of him as a kind of Superman."

Thinley, who is a monk, met Paljor in Delhi days before he was due to leave; he gave his brother a blessing before telling him goodbye. "He'd just passed his health exam, and he was so excited to go to Tibet," Thinley says. "He wasn't nervous at all. He was really happy about all of this."

Thinley was the last family member to see Paljor alive.

**

Paljor was young, strong and experienced, but Everest presents multitudes of ways to take the life of even the most well prepared climber – falls, avalanches, exposure and more. The body also baulks at the insults it endures on the mountain. Sudden death – from heart attacks, strokes, irregular heart beat, asthma or exacerbation of other pre-existing conditions – is not uncommon, and lack of oxygen can trigger acute pulmonary or cerebral edema: life-threatening conditions that occur when blood vessels begin leaking fluid into the lungs or brain.

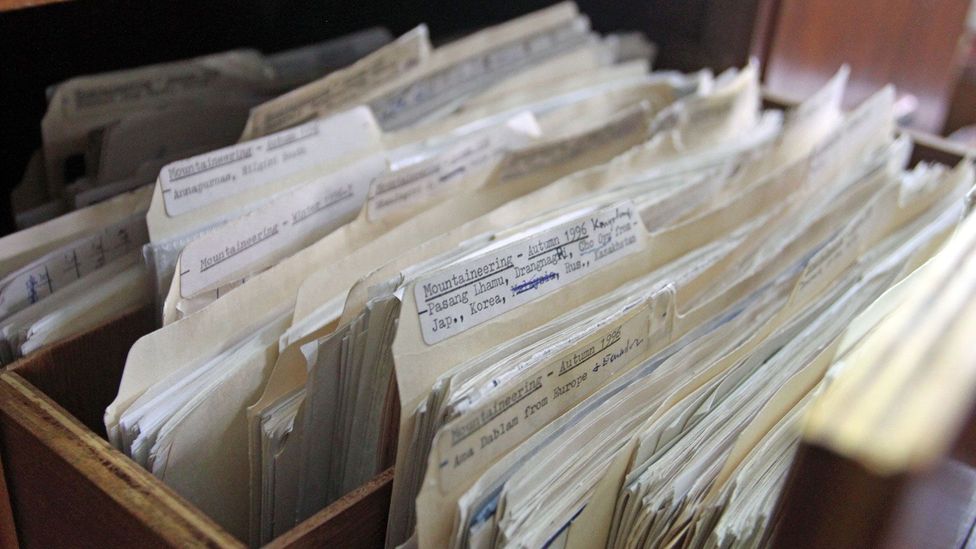

Documentation for Paljor: resident of Sakti, climber, no children - from the files of Elizabeth Hawley

Not everyone on the mountain shares the same odds of dying under any given circumstance, however. In a retrospective study of 212 climbing deaths on Everest from 1921 to 2006, Paul Firth, an anesthesiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues found that most Sherpa deaths occur at lower altitudes, reflecting the unavoidable risk of traversing the Khumbu icefall – an unstable glacier field laden with house-sized ice blocks and gaping crevasses. Deaths at higher elevations, on the other hand, almost entirely belonged to paying clients and Western guides, and more than 50% of deaths above 8,000m (26,000ft) occurred after climbers had summited and were on their way back down. "I was surprised at how few Sherpas have died high up," Firth says. "But the numbers are glaringly obvious."

These findings likely reflect a multitude of factors, including Sherpas' possible superior adaptations to hypoxic conditions, their greater experience on Everest and their lack of vulnerability to summit fever – an overwhelming desire to reach a mountain's peak that causes climbers to disregard safety. "People make decisions based on success, not on survival," says Ed Viesturs, the first American to have climbed all 14 of the world's 8,000m peaks, and the fifth person to do so without supplemental oxygen.

A medal awarded after Paljor's death

When Mark Jenkins, a journalist, author and adventurer in Wyoming, was on Everest in 2012, five people died on a single day. Sherpas he interviewed told him that most of the fatalities belonged to clients who had refused to turn around. "Your Sherpa will tell you, 'You're too slow, you have to turn around or you'll die,'" he says. "And some people don't."

"Mountains don't kill people, people kill themselves," he says.

(Read part two in this series, about the problem of Everest's 200+ bodies.)

Viesturs, who once ended a climb on Everest within 100m (300ft) of the summit because conditions did not look good, credits his survival to always listening to the mountain and knowing when to turn back. "My rule was that climbing had to be a round trip," he says. But many of Everest's victims, Firth contends, are likely people who don't recognise early warning signs because they lack sufficient experience to know what's normal, or else are experienced climbers whose judgment is muddled by the effects of altitude. By the time they realise they are in trouble, it's too late.

Kathmandu, where many Everest journeys begin

Jenkins estimates that half the climbers on Everest today do not belong there. "Its not my opinion, it's just a fact," he says. "The highest some of them have ever been is up a skyscraper."

"Without Sherpas, 98% of people who climb Everest couldn't," agrees Billi Bierling, a Kathmandu-based journalist, climber and personal assistant for Elizabeth Hawley, a former journalist, now 91, who has been chronicling Himalayan expeditions since the 1960s.

Files of expeditions, kept by Elizabeth Hawley

On Everest, things were proceeding without a hitch for Paljor and his comrades. The Indian expedition was well connected on the mountain, with a luxurious communal tent that all climbers, regardless of nationality, were welcome to visit.

Commandant Mohinder Singh, who led the team, told me about the expedition at his home outside of San Francisco, where he now manages an apartment complex: "We were the top class in the world."

Mohinder Singh and his wife at their home outside of San Francisco

For his strength and enthusiasm, Singh selected Paljor to be part of the first summit attack team, along with climbing partners Tsewang Smanla and Dorje Morup, and deputy leader Harbhajan Singh. "Paljor wanted to do many things in his life," says Singh, who believes the young man looked up to him as a sort of father figure.

He recalls Paljor as being very talkative, "like a child," and that he loved to attempt difficult rock climbs. "He looked like a monkey when he climbed," Singh says. He also remembers Paljor's love of roast chicken; his tendency to sing in his free time; and that he was always volunteering to take on difficult jobs. "He was very helpful like that," Singh says.

Singh was confident in Paljor, Morup and Smanla's skills – they were all from Ladakh, and had all proven themselves in the field. However, almost immediately, the expedition was marred by "mistake after mistake," in which the climbers "failed to follow clear instructions," Singh later reported in his official account of the events.

The problems started on the morning of 10 May, when the team was delayed by strong wind and then overslept. They did not set out from Camp VI until 08:00, rather than 03:30 as planned. Given the extremely tardy start, they decided to move further up the mountain to fix ropes rather than attempt the summit, since doing so would guarantee descending through the Death Zone in the dark – the area above 8,000m where climbers often lose their lives.

Harbhajan Singh, deputy team leader, and the only survivor of the expedition

By 14:30, the team had made significant progress, but the wind had begun to pick up again. Singh had given the team strict orders to turn around at 14:30, or 15:00 at the latest. Harbhajan Singh, however, was lagging far behind the three Ladakhi men. When he signaled for them to stop and return to camp, they either did not see him or ignored him. Watching as they pushed on, the frostbitten Harbhajan Singh had no choice but to descend back to Camp VI without them.

Speaking about this moment 19 years later from his bright office in New Delhi, Harbhajan Singh, now an inspector general at the ITBP and recipient of the Padma Shri, India's fourth-highest award, gets a distant look in his eyes.

"When we lost these three people, I was the fourth, I was with them," he says, gazing beyond me. "I'm in front of you today, but if I would have tried, I would be gone. It's only God's gift that I am alive."

Summit fever, he suspects, had overtaken his men.

Everest has killed nearly 300 people (Credit: Getty Images)

At last, at 15:00 that afternoon, an anxious Singh, awaiting news from Advanced Base Camp, heard his walkie-talkie sputter to life. It was Smanla.

"Sir, we are heading towards the summit," Smanla announced.

Singh was taken aback. "Oh no! The weather is very deceptive, bad."

Smanla was not to be dissuaded, however, and pointed out that the summit was less than an hour away and that all three men felt fit.

"Don't be overconfident," Singh insisted. "Listen to me. Please come down. The sun is going to set."

Smanla shrugged off the warnings, and put Paljor on the phone. "Sir, please allow us to go up!" Paljor said, his voice brimming with pride. But just then, the radio cut off.

It wasn't until 17:35 that Singh heard back from his men. A flood of relief and excitement washed over him as Smanla announced that he, Paljor and Morup were standing on the summit. Even as Singh stressed the importance of returning as soon as possible, he began looking forward to the triumphant message that he would send to New Delhi announcing his team's victory.

Celebrations immediately ensued, both at home and at camp. The men had just set a record for their country. Whether Paljor and his teammates actually summited, however, was later called into question. Krakauer and others suspect that the men unintentionally stopped 150m (500ft) short of the peak, believing – due to increasingly bad weather and the mental haze of high altitude – that they had reached the top. Despite the uncertainty, however, they are credited with the ascent, as the trophies Tashi Angmo later received on behalf of her dead son attest. As Singh says: "They made it, they accepted that they made it, and I confirmed it."

In their quest to reach the top, many climbers get 'summit fever', disregarding risks (Credit: Rex)

Yet the jubilant feeling at camp was to be short-lived. Shortly after Smanla called, the weather, which had been steadily deteriorating, broke. The infamous 1996 blizzard had arrived, cloaking the mountain in a fury of snow and wind. Trying to keep his fears at bay, Singh told himself that the men would be fine, that they had dealt with worst weather in the past. If they hustled, they could even make it back to Camp VI by midnight. "However," he later recalled, "this did not happen."

Ethics at 8,000m

By 20:00 on the night of Smanla, Paljor and Morup's ascent, Singh could no longer contain his worry. According to his official account, he decided to approach a Japanese commercial climbing team from Fukuoka for help. Two of the team's climbers, Hiroshi Hanada and Eisuke Shigekawa, planned to leave for the summit that night.

Using a Sherpa who spoke some Japanese to help translate the conversation, Singh "impressed upon [the Japanese leader] the seriousness of the situation." Singh reports that, in his presence, the Japanese leader radioed his team at Camp VI to explain the situation, and then told Singh that the Japanese climbers would do all they could to help the stranded Indians if they encountered them on their way to the summit. "The Sherpa [translator] ensured us on his behalf that the Japanese would treat this crisis as their own," Singh writes.

By morning, the storm had died down and the Japanese were able to set out for the summit. At 09:00, the leader of their team informed Singh that his two climbers had encountered Morup, who was frostbitten and lying in the snow. They had helped him clip into the next fixed line, but then continued on their push to the summit. "We were dismayed," Singh writes. "The black tea that the Japanese served us tasted black indeed."

Two hours later, under a "clear and serene sky," the two Japanese climbers and their three Sherpas passed Smanla and Paljor, but again did not stop or render any help. "Why did they not give even a drop of water to our dying men? What about mountaineering ethics?" Singh writes. "The Japanese had left us with little hope."

The Japanese team, however, later contested this version of events. The "baseless accusations" made against them, they stressed, entirely hinged on flawed, one-sided information. Back in Japan, they held a press conference and issued an official report stating that Shigekawa and Hanada had never been informed that the Indian climbers were in any sort of trouble. While they did encounter several climbers on their way to the summit, Hanada said, "we did not see anybody who seemed to be in trouble or dying."

The report they issued also emphasised that above 8,000m, "it is common sense" that every climber should be held accountable for their actions, "even on the brink of death."

The climber's code of ethics, issued by the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation, specifies "helping someone in trouble has absolute priority over reaching goals we set for ourselves in the mountain." Most take this to heart. "Saving one life is more important than summiting Everest 100 times," says Serap Jangbu Sherpa, the first person to climb all eight of Nepal's 8,000m peaks, and the first to summit K2 twice in one year. "We can always go back and summit, but a lost life never comes back."

Captain MS Kohli, at his hotel in New Delhi, the Legend Inn

"To say that everyone should look after himself, that no one should help another team is nonsense," adds Captain MS Kohli, a mountaineer who in 1965 led India's first successful expedition to summit Mount Everest. "That is absolutely against the spirit of mountaineering."

That simple rule becomes more complicated, however, when commercial clients are involved. After paying many thousands of dollars for safe passage to the summit, it's less clear what those climbers' role is, should they encounter someone in need and likewise, it's also unclear to what extent a guide can be depended on to save a client's life at the possible cost of his own.

Add to that the fact that, above 8,000m, decision-making and critical thinking skills are severely impaired. "The nearest thing I can compare it to is like being quite seriously drunk, but not fun," Firth says. As oxygen diminishes, plans and morals formulated at lower elevations often lose their clarity.

Equipment used by Captain MS Kohli on Everest ascents

"People are so fascinated by this when they're sitting in their living room reading Outside magazine, but the dynamics of what it's like to be up there are really hard to comprehend from down here," says mountaineer Gulnur Tumbat, an associate professor of marketing at San Francisco State University. Even if a climber wanted to help someone in need, she points out, he would likely be putting his own life on the line to do so. "Above 7,000 or 8,000m, there's not much you can do," she says. After experiencing the effects of high altitude herself, she was not surprised to find in her research that people at Everest tend to be individualistic. "There's actually not that much camaraderie up high on the mountain," she says. "I'm not saying it's a bad thing or a good thing – it's almost necessary to be that way, given the conditions."

It also doesn't help that, for many people – no doubt Shigekawa and Hanada included – a trip to Everest is seen as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The amount of time, money and energy invested in the mountain can encourage selfish and reckless decision-making. "There's a mystique to Everest where people come to the conclusion that traditional rules don't apply, whether that means how much risk they're willing to take or what the value of reaching the top of the mountain is to them," says Christopher Kayes, chair and professor of management at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C. "I think the closer you get to your goal, the more likely you are to come up with rationalisations for foregoing morals or values."

In some cases, he continues, it might "literally mean throwing caution to the wind." In others, it might mean leaving a fallen climber behind who is deemed beyond helping. (Bierling points out, however, that rescues happen every year – they just don't make the news like the deaths do.)

Cloud of doubt

Neither Shigekawa nor Hanada responded to interview requests for this story, but Koji Yada, one of the two men's climbing leaders, recalled the incident to me when I met him in Fukuoka. "As I understood the situation, the [Indian] climbers were wearing heavy equipment, so it was difficult to tell who they were," he says, adding that he does not know whether Shigekawa or Hanada sensed that the unidentified climbers were in distress.

"I have no idea what I would do if I were in the same situation [as them], but I cannot help thinking that I could do nothing," he says. "Someone might say that's inhuman and selfish, but there's nothing I can do."

"Eight thousand metres and up is a totally different world," he continues. "We often use the word self-responsibility to describe the situation there."

What responsibility should climbers have for their fellow mountaineers? (Credit: Rex)

As with so much that happens on Everest, the events of that May day in 1996 are no doubt clouded by subjectivity, self-interest and the mind-clouding effects of high altitude, and we will likely never really know what transpired in the last hours of Paljor, Smanla and Morup's lives.

When things do go awry, media frenzies ensue, and the typical reaction is to analyse what went wrong and then distill a handful of lessons learned. A few business schools even use the 1996 Everest disaster as a teaching tool. But some experts believe that there simply is no making sense of what transpires above 8,000m.

"It is difficult to know for sure what really happens during a climbing disaster among teams of ambitious people at 8,000m in howling winds and in a state of hypoxia, dehydration and exhaustion," says Michael Elmes, a professor of organisational studies at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts. "I don't think events like the 1996 disaster can be analysed or anticipated, and I'm doubtful that there are ways to prevent future disasters."

**

Tashi Angmo has trouble recollecting the days following her son's death. She does remember two men from the Indo-Tibetan Border Police coming to her door and asking if she was Paljor's mother. They told her that there had been an accident on Everest, and that he was missing. The ITBP had deployed a battalion to search for him, they said, and had even sent a helicopter. But despite their efforts, he seemed to have vanished.

Looking back now, she wonders if the men were telling the truth. "Maybe they looked for him and maybe they didn't," she says. "But if the right effort had been put in, I believe that he definitely could have been found and saved."

Leh is home to a branch of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police, Paljor's former employer

After receiving the news, because there was no body, and because the officers told Tashi Angmo that her son was missing – not dead – she spent the next two days travelling to all the local monasteries, performing thimchol, an offering for wellbeing. "It would have been better if they had found the body," she says. "I kept hoping he'd come back, because they never found the body."

Eventually, though, her relatives insisted that she face reality. Paljor was not going to be rescued, and he would not be coming home. "'Missing' is a term the ITBP is using to relieve you," they gently told her.

The family eventually held a funeral and also attended a ceremony put on by the ITBP in honour of the three Ladakhi men. "I was like a dead body," says Tashi Angmo.

Her grieving process was further exacerbated by bitterness that soon developed toward the ITBP. Though officials promised the family that they would be well taken care of, they received an insurance sum of only $3,690, followed by pension payouts every other month of about $36.00 – an amount, Tashi Angmo says, that "won't even last three days."

"Shame on ITBP! They are not good!" she told me, weeping. "A child is priceless, money is nothing. But we are the affected family. I lost my child. They should honour their promises."

Though Paljor died a hero, his family received pittance while his body would remain on the mountain, becoming a morbid fixture of the landscape. When Everest takes a life, it also keeps it. Eventually, he became Green Boots – a climber without a name that people would pass by every year en-route to their own personal glory.

It wasn't, however, the last chapter in Paljor's story…decades later, he would disappear. In part two, I will investigate what happened next, the growing problem of the 200+ bodies still on Everest – and the intriguing psychological reasons why people continue to climb this deadly mountain.

Body People Yeah, Body People Let Die to See You Baby Baby...

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20151008-the-tragic-story-of-mt-everests-most-famous-dead-body

0 Response to "Body People Yeah, Body People Let Die to See You Baby Baby..."

Post a Comment